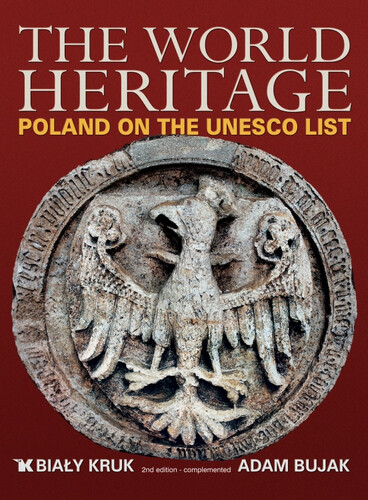

Światowe dziedzictwo. Polska na liście UNESCO (ang) // The World heritage. Poland on the UNESCO List.

| liczba stron: | 336 |

| obwoluta: | tak |

| format: | 235x320 mm |

| papier: | 170 g kreda błysk |

| oprawa: | twarda płócienna, tłoczenia, złocenia |

| data wydania: | 05-03-2007 |

| ISBN: | 978-83-60292-32-9 |

dodaj do przechowalni

dodaj do przechowalni

Monumentalne dzieło z 400 wysokiej jakości fotografiami znakomitego artysty Adama Bujaka. Ukazuje światowej klasy polskie zabytki i unikatowe relikty pierwotnej przyrody. Prezentuje polskie obiekty umieszczone na prestiżowej liście Światowego Dziedzictwa Kulturalnego i Naturalnego UNESCO.

Na zdjęciach zobaczymy m.in. wiekowe mury Krakowa, grę świateł w kryształach wielickiej soli, brodzące w śniegu białowieskie żubry, malowniczą Starówkę w Warszawie, kolorowe kamieniczki Zamościa, dostojny gotyk Torunia, krzyżacką twierdzę w Malborku, dróżki Polskiej Kalwarii, niezwykłe dolnośląskie Kościoły Pokoju, pachnące drewnem gotyckie kościółki Małopolski, a także poruszające świadectwo męczeństwa więźniów Oświęcimia. Album powstał z myślą o artystycznej promocji Polski na całym świecie. Wspaniała propozycja na wakacyjną lekturę.

Album powstał z myślą o artystycznej promocji Polski na całym świecie. Wspaniała propozycja na wakacyjną lekturę.

Zamość is a remarkable town. This may sound like a truism, but please keep in mind that had it not been for its specific qualities, Zamość would not have been placed on the UNESCO World Cultural and Heritage List in 1992. It is exhaustively described in popular tourist guides. Expert scientific studies analyse all the aspect of its history in great detail. So why is it so famous? Why does it evoke so much interest? What makes it so enchanting to both Polish and foreign visitors? To cut the long story short, Zamość is a remarkable example of an utopian model of a perfect town. But what does that really mean? The meaning seems to become apparent from the first glance. The urban arrangement and structures of Zamość were so carefully thought out as to perfectly serve their inhabitants. Even though utilitarian purposes remained within the wide scope of attention during the city’s design phase, it was not this type of ”ideal” that was the primary focus of its creators. Ideal – means fully harmonious in a higher and symbolic sense of the word. In architecture, perfection is expressed by pure, unadulterated geometric forms. They have been attributed all sorts of various meanings since ancient times. Arranged together they formed a sort of a handbook, used by urban planners and architects enchanted by the idea of creating works equal to the unmatched creations of God himself. The challenge to design perfect towns, churches, palaces, strongholds, and also hospitals, universities and other public buildings were taken up especially eagerly by the Italian Renaissance artists. Italy is full of such endeavours. Some are more successful than others. Many have never been finished. Bernardo Morando (ca. 1540-1600 or 1601), author of the general urban design and of a significant part of Zamość development also came from Italy. More specifically from Padua. He arrived in Poland – just like many of his countrymen – to find profitable commissions. After his 1569 arrival, he found employment in Warsaw, at the construction of the new royal residence. However, the greatest achievement of his life was made possible thanks to Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605), who in 1578 entrusted him with a commission, the sort of which is seldom proposed even to the greatest architects – the creation of a grand (for its day) city-stronghold, a centre of the vast latifundium and a clear demonstration of its founder and patron’s grandiosity. Jan Zamoyski is a figure shrouded in the aura of fame. He was an eminent senator, politician, commander, humanist, and a patron of science, literature and art. As the Crown chancellor, in many respects he set the directions for Polish politics during the reign of King Stephen Bathory. He made his mark especially during the interregnum, and the subsequent unexpected flight of Henri Valois from Poland. Commanding the loyal army of the lawfully elected King Sigismund III, he crushed the army of the Archduke Maximillian Hapsburg – pretender to the Polish throne – in the Battle of Byczyna (1587). Zamoyski was highly educated. He studied in Paris, Strasburg and Padua, and composed literary works (including the Latin epigrams placed on Zamość edifices). He was a patron of the sciences and personally saw to their popularisation by establishing the famous Zamoyski Academy in 1594. This was made possible due to his enormous wealth – his estates covered 6,500 km2 and brought him nearly 200 thousand zloty of income annually – a rather impressive amount by contemporary standards. Let us get back from this tangent and concentrate on Zamość. Its foundation charter was issued on April 10, 1580. Construction of a city, planned for five thousand inhabitants, had to be spread out over some period of time. The work of Jan Zamoyski, thus had to be continued by the successive lords of Zamość (such as Tomasz, direct heir of the great benefactor) and eminent architects – such as Jan Jaroszewicz and Jan MichaΠ Link. Both of them were active in the seventeenth century and placed their mark on the city’s current shape. The city, of course, did not survive unchanged to our times. It was significantly transformed in the first half of the nineteenth century, when many of the buildings were given a cold and austere Classicistic shape (one of them being the Town Hall). Also then, the Zamość fortifications were altered to make it a mighty fortress. Attempts to return the town to its past splendour were taken up several times. The original Town Hall fa˜ade was restored in the years 1936-1938. Attics of the stone tenement houses were restored towards the end of the 1970s. More work was done recently, prior to the 1999 visit by the Pope, John Paul II. The city plan is formed on a pentagonal layout (slightly deformed due to the local topography), adjoined to a smaller rectangle. The benefactor’s residence was located in a separate area. This exquisite building complex is today known only from paintings and illustrations. Using the Renaissance anthropomorphic parallel, it was the head of the urban organism formed to resemble a human body. The heart of the town is formed by the still surviving Collegiate Church (now upgraded to a cathedral), in which the great benefactor found his final resting place. A thorough observer, conscious of the Renaissance architecture ideals, will find the cathedral to be a realisation of pure, geometric harmony, where a visitor will find pleasure in taking in the numerous details and age-spanning furnishings. The artistic standard of the cathedral’s past furnishings is seen in the former main altar – currently located in Tarnogród – which includes paintings by the Venetian, Domenico Tintoretti. The town also boasts a vast array of other Catholic churches. There is also an Uniate Orthodox church attended by the Ruthenian minority, an Armenian church, and a synagogue for the Jewish community. The Town Square, also called the Grand Square (some100 meterson side), which usually served mercantile purposes, was spoken of as being the town’s navel. It was accompanied by two smaller market squares. The Town Hall, together with its soaring tower, symbolised the town’s independence and administrative power, as executed by the City Council. Around the Town Square and alongside the adjoining streets, there are lavishly decorated “town square houses”, ringed with low arcades. Next to the fa˜ades ornamented with proper, stencilled, Dutch styled, Mannerist ferruled décor, there are some buildings thickly covered with dough-like ivy leaves, and precarious figures of saints, looking as if sculpted in marzipan by some pastry chef, instead of an architect or a sculptor. Despite, or perhaps thanks to their naivety they cheer our eyes, sometimes provoking laughter with their comic shapes. They add a homely, provincial touch to this ideal, ”Italian” city. The city design was finished off with a partly preserved circuit of modern bastion fortifications, built on the new Italian system (symbolically perceived as the city’s arms), with impressive gates modelled on the Roman triumphal arches. They were additionally strengthened by moats and an artificial lake. Let us close this short presentation of the town with an opinion stated in 1598 by the Dutch humanist, Georgius Dousa: ”Nothing can better testify to his [Jan Zamoyski’s] great love for his homeland than this city, which he constructed using his own resources. He raised it from the foundations up, fortified it with mighty walls and towers against the raids of enemies, and finally called it Zamość in his own name. He thus left behind a reminder, more solid then the pyramids and monuments, not only for Poland, but for entire Europe.”