Ostatnio oglądane

Ostatnio oglądane

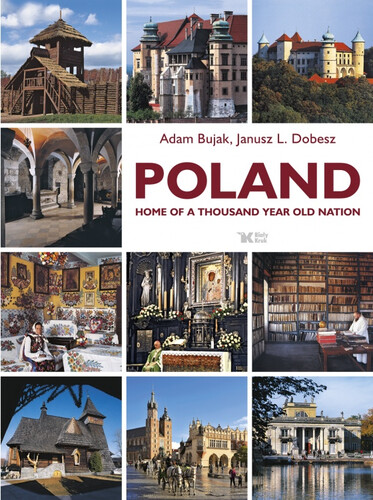

Polska. Dom tysiącletniego narodu (ang) // Poland. Home of a thousand year old nation

| data wydania: | 09-12-2014 |

| ISBN: | 978-83-7553-177-0 |

dodaj do przechowalni

dodaj do przechowalni

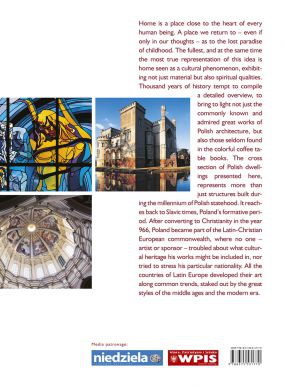

Dom jest miejscem bardzo bliskim każdemu człowiekowi, a jako zjawisko kulturowe, posiada oprócz postaci materialnej również wartość duchową. Tysiąc lat historii skłania do ogólniejszej refleksji i kusi, by przypomnieć nie tylko powszechnie znane i podziwiane, wspaniałe dzieła architektury polskiej, ale zaprezentować również te obiekty, które zwykle są pomijane w barwnych albumach. Prezentację rozpoczynamy od domostw naszych słowiańskich praprzodków – jaskiń i grot, drewnianych biskupińskich budowli, by następnie pokazać różnorodność zamków, pałaców, domów mieszczańskich, wiejskiej zabudowy, dworków, rynków, domów robotniczych, współczesnej architektury mieszkalnej. Pokazujemy też klasztory jako miejsca zamieszkania wspólnot zakonnych oraz kościoły – domy Boże.

Album z fotografiami Adama Bujaka wstępem opatrzył znawca tematu prof. Janusz Dobesz z Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.

Home of a Thousand Year Old Nation 6

Caves, Towns and Castels 28

Wawel 42

Palaces 56

Manors 92

Regions 98

Urban Diversity 120

House of a Worker 142

Market Squares 148

Warsaw 154

Cracow of the 19th and 20th c. 162

Cloisters 174

Jasna Góra 200

Cementeries 206

House of God 216

Symbols of Polish Unity

To wrap up the list of presented castles, we will mention the “Castle of the President of the Polish Republic in Wisła” – a fascinating structure for many reasons. This unusual house, rising from the southern slope of Zadni Groń in the Beskid Wiślański mountain range, was built according to a concept by Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, who offered his services free of charge. This generous offer allowed the district government of Silesia to do away with an earlier planned bidding in the form of an architectural competition. The blueprints were ready in the summer of 1928. The mountainside seat of the Polish president was itself finished in 1930.

The fact of its being called a castle is explained by its form. Situated on a slope, it boasts a massive, buttressed and bastion-shaped, stone terrace. Traditions of defensive architecture can be seen in the presence of two towers, the use of stone wall-lining and medieval-styled details, such as arched windows or the recessing portal bearing an image of the Silesian Eagle.

Planning the interiors and furnishings, the architect entrusted to Andrzej Pronaszko – an ace of contemporary Polish avant-garde. Even today we are astounded by the boldness and maturity in taste, exhibited by the designers and even more by the investors who approved the daring and unusual, for the times, forms and colors. Brought to fruition was a set of unique metal furniture, made of wrought and chromed steel pipes, with glass or wooden shelving and tabletops, fabrics and tapestries. Standing on Poland’s “Western Frontier”, the castle was symbolically supposed to integrate Silesia with the rest of the country. It was even opened up to visitors. World War II spared the structure, even part of the original

furnishings survived. What suffered however, were the ideological values, which shined so brightly at its conception. In the 1950s it functioned as a sort of a place of political exile for, fallen from grace, party dignitaries. Later on, it became a holiday resort for the governing elites. Today, after the restoration finished in 2005, it is again the Castle of the President of the Polish Republic.

Alongside the rectangular shaped palace, there appeared a new variation, with a central, round, and covered with illuminated domes, salon. It referred straight back to the famous Palladio of the sixteenth century – the Rotonda villa in Vincenza. This model, introduced by Domenico Merlini in Królikarnia never gained particular popularity. It was not too comfortable, and in addition alien to Polish tradition.

The only architect said to follow Merlini was probably Stanisław Zawadzki, who in the years 1795-1800 erected the Skórzewski family palace in Lubostroń.

Floor of the rotundal hall was decorated with the crests of both the Crown and Lithuania. Its walls sported four relief sculptures: “The defeat at Płowce, suffered by the Teutonic Order at the hands of Ladislaus the Elbow-High”, “Ladislaus Jagiello’s victory over the Teutonic Order near Koronów”, “Queen Hedwig bestowing privileges on the Teutonic Order in Inowrocław in 1396” and “Marianna Skórzewska presenting the blueprints of Bydgoszcz water locks for the approval of Frederyk Wilhelm”.