Opuszczeni bohaterowie Powstania Warszawskiego (ang) // Abandoned Heroes of the Warsaw Uprising

| liczba stron: | 128 |

| obwoluta: | nie |

| format: | 235x290 mm |

| papier: | 150 g kreda |

| oprawa: | twarda |

| data wydania: | 21-02-2008 |

| ISBN: | 978-83-75530-22-3 |

dodaj do przechowalni

dodaj do przechowalni

Żywa lekcja historii i patriotyzmu!

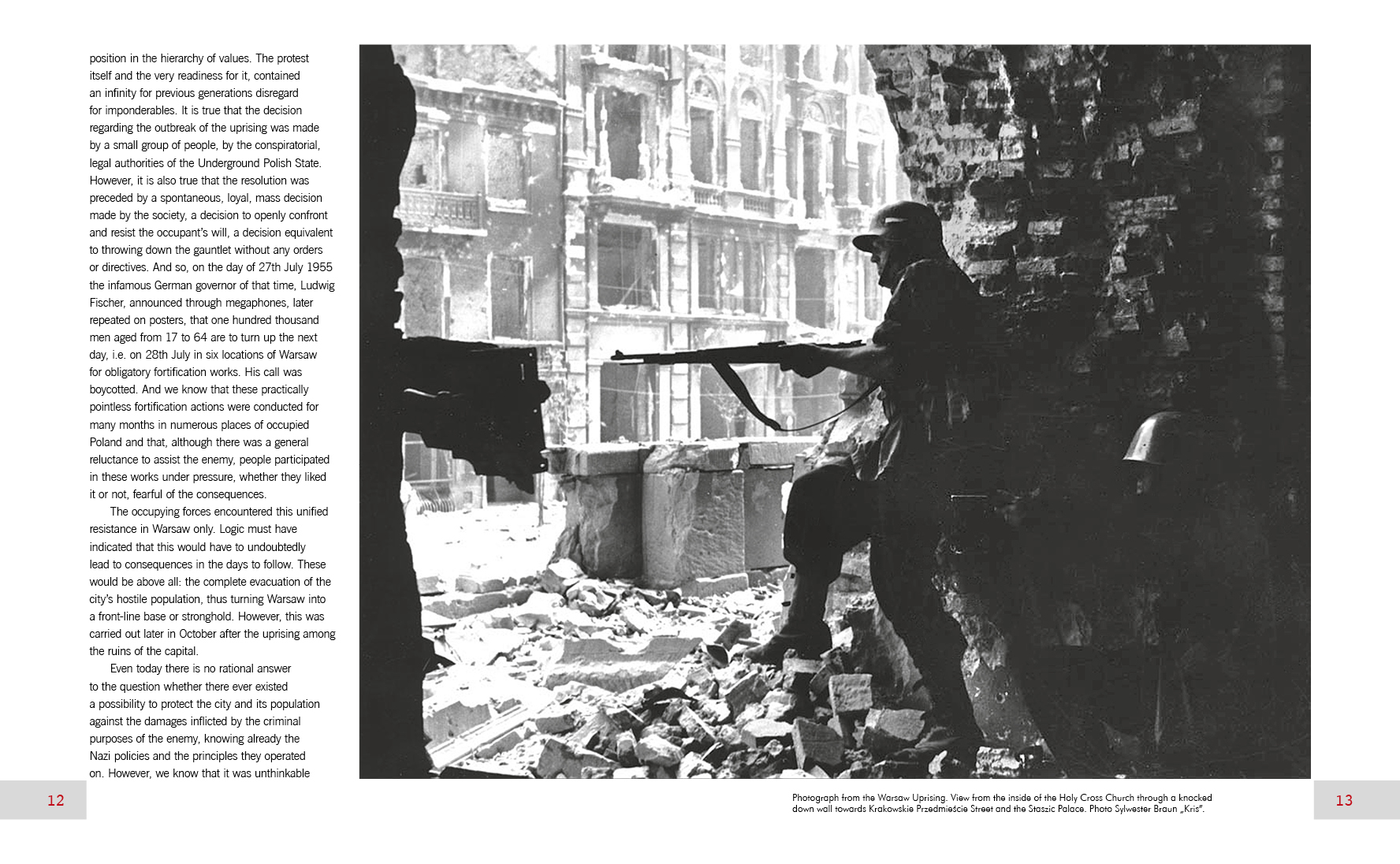

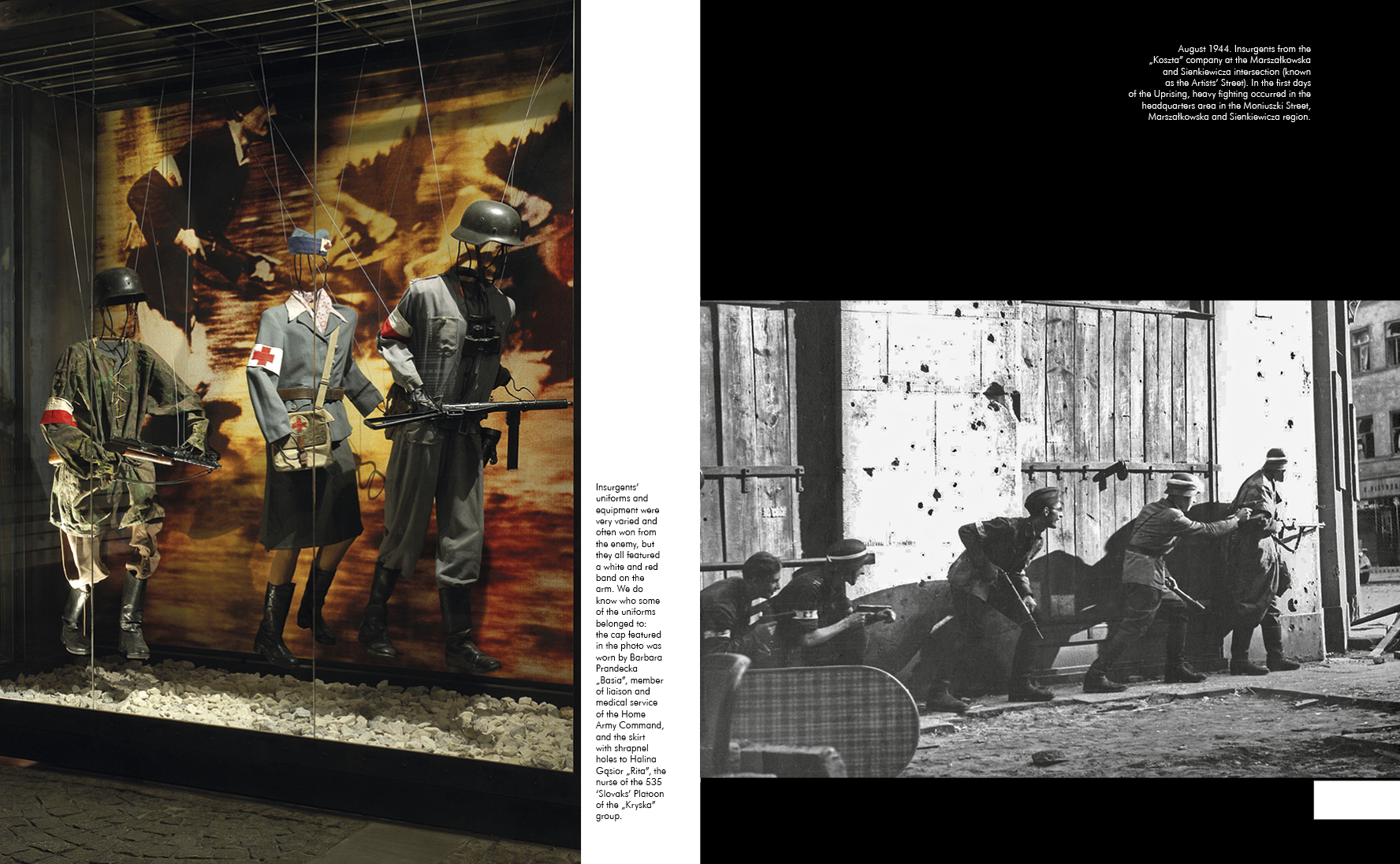

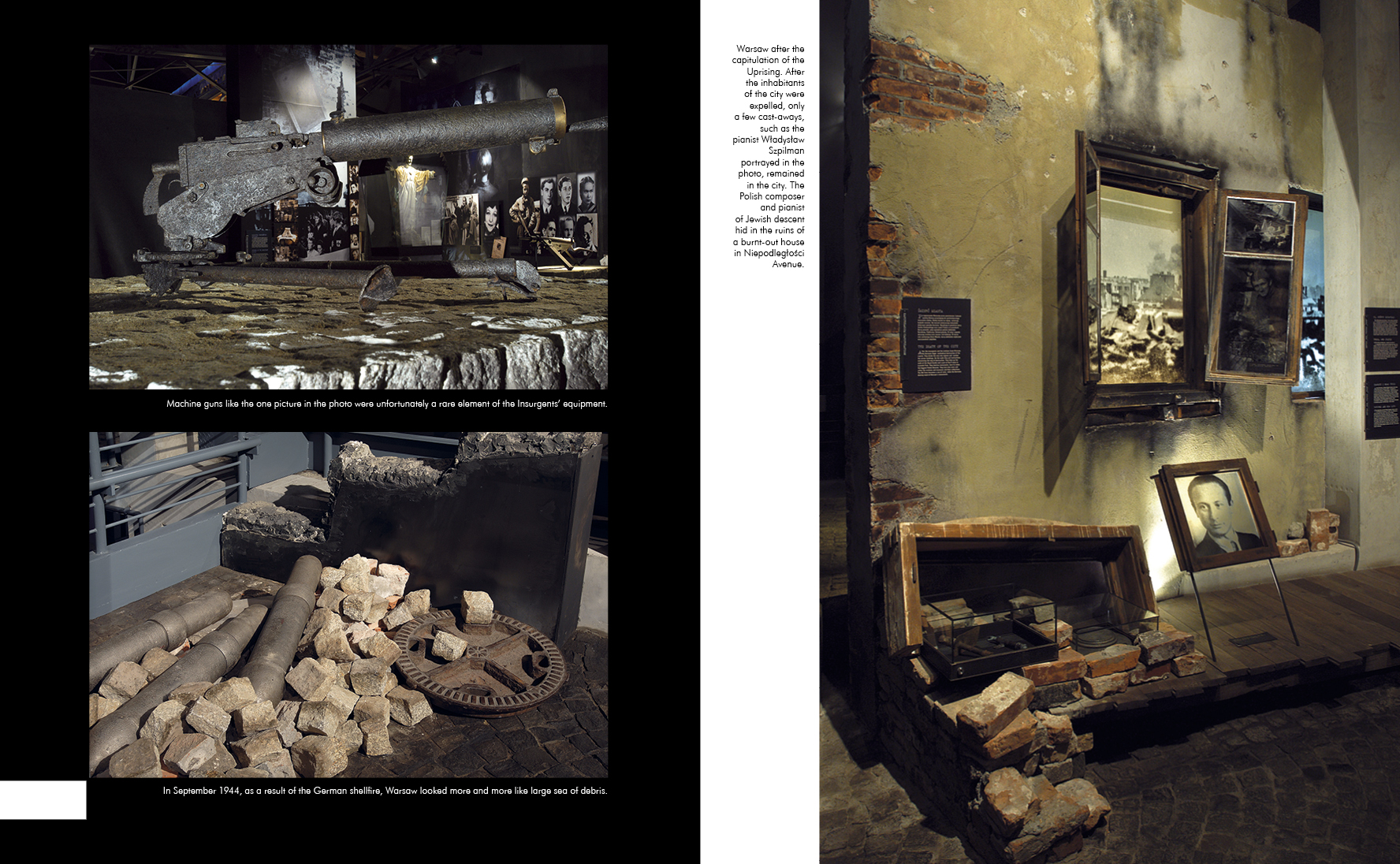

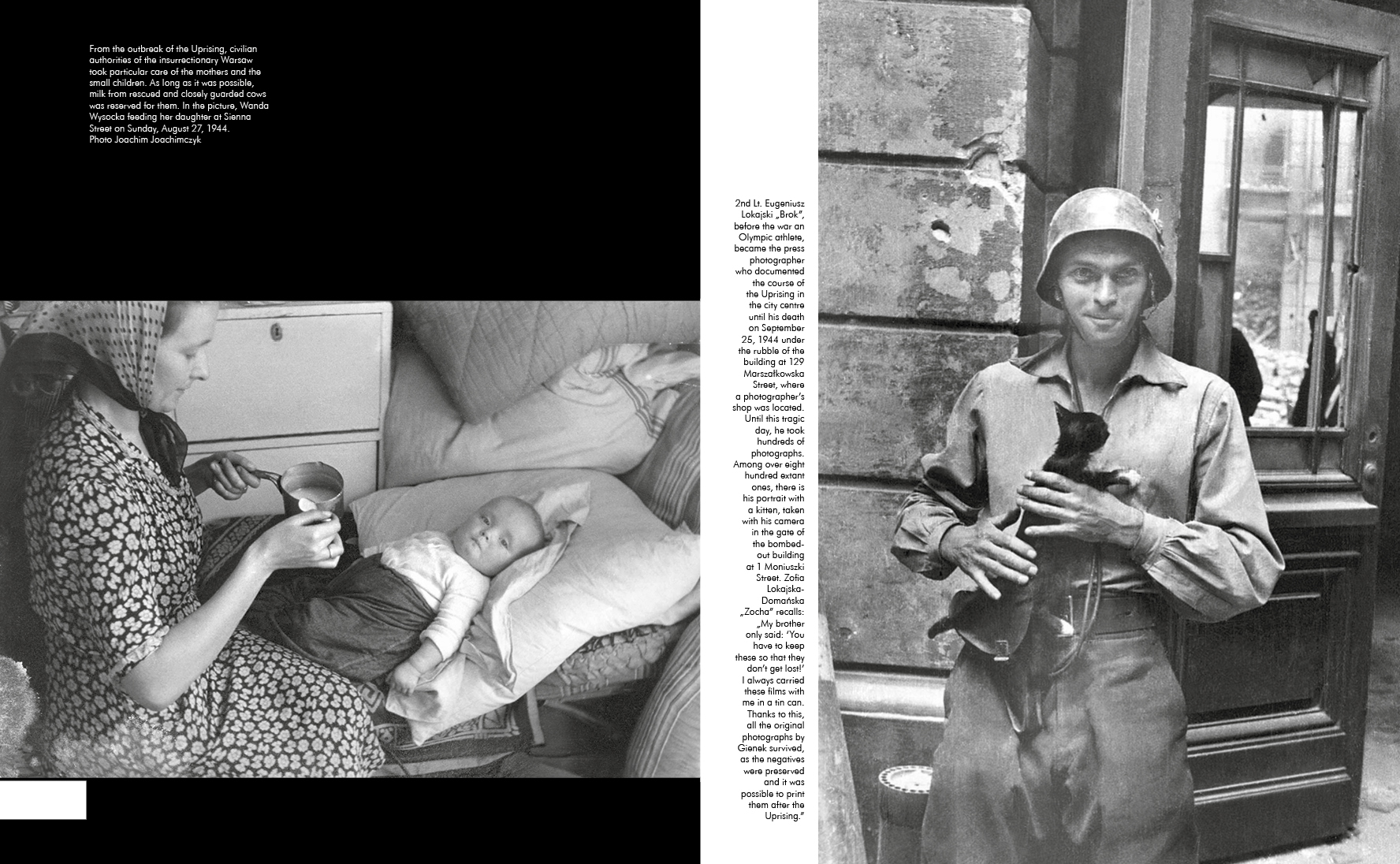

Frapujący tekst prof. Władysława Bartoszewskiego przybliżający i analizujący Powstanie Warszawskie. Ponad 100 emocjonujących fotografii: Adama Bujaka oraz powstańczego fotoreportera Eugeniusza Lokajskiego "Broka". Na zdjęciach m.in. słynne ekspozycje, wnętrza i wystawy Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego, zdjęcia walczącej Stolicy, fragmenty murów i ruin powstańczej Warszawy, listy powstańcze, życie codzienne pod obstrzałem wroga - powstańcze śluby, chrzty, działalność poczty powstańczej, dramatyczna walka o przeżycie nowonarodzonych dzieci.

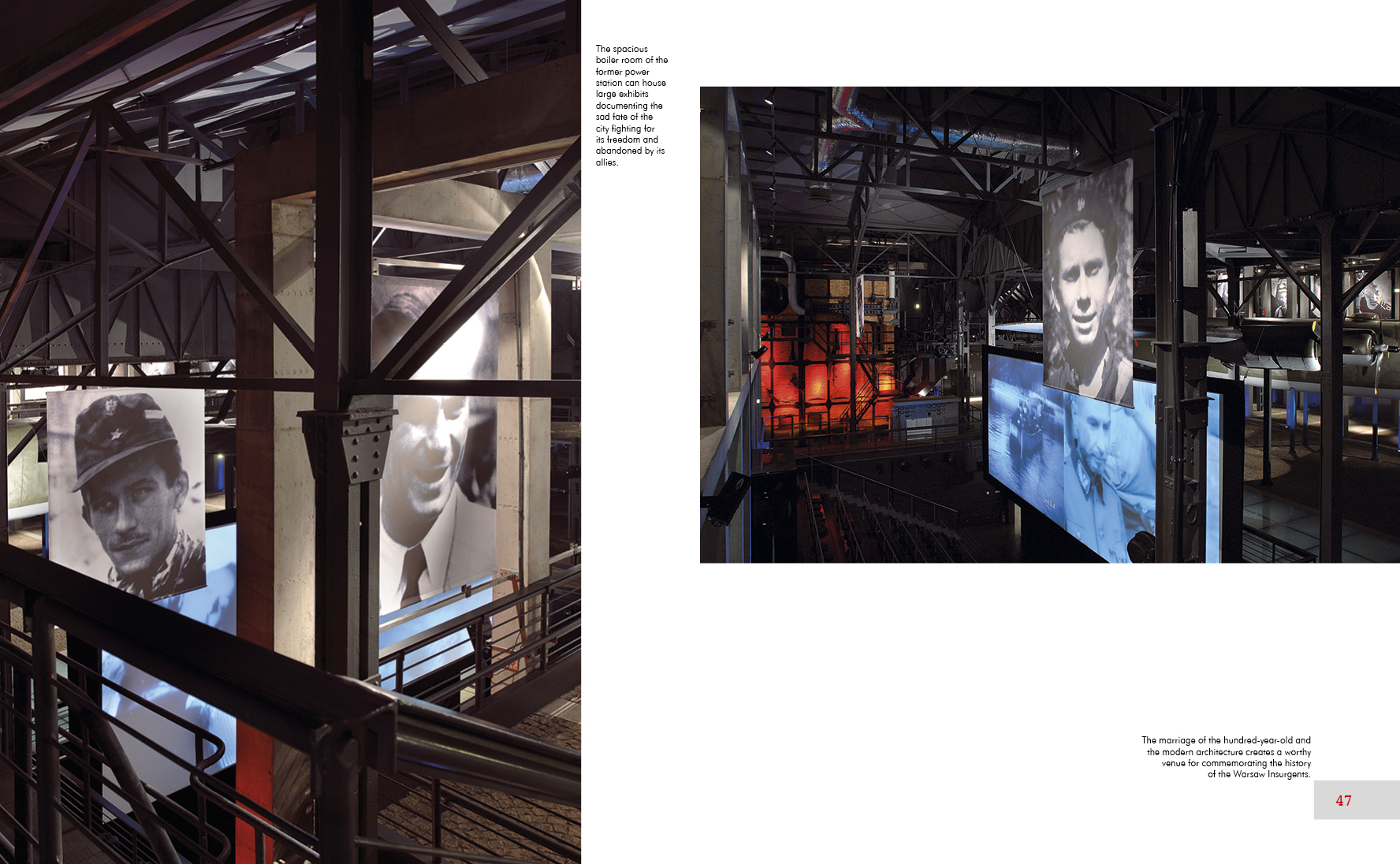

"Przekroczyłem próg i natychmiast zostałem odcięty od świata zewnętrznego. Wszedłem do budynku i zostałem wprost obezwładniony. Drzwi zatrzasnęły się za mną, a ja w tym samym momencie pozostawiłem za sobą nie tylko dzienne światło, ale i nieistotną codzienność. Odczuwali to samo inni zwiedzający, dzięki czemu atmosfera była niezwykła. Natychmiast po wejściu wyciszali się w zadumie, rozmawiając co najwyżej szeptem. […]

W przeciwieństwie do wielu innych podobnych miejsc, tutaj czuje się i przeżywa historię. Wyposażenie hal i pawilonów budzi emocje, skądinąd też dlatego, że wielu Polaków ma osobiste powiązania z Powstaniem. […]

Chodząc pośród murów Muzeum widziałem wiele twarzy młodych mężczyzn i kobiet, uwiecznionych na zdjęciach. Wszyscy walczyli w Powstaniu, a ci, którzy przeżyli są dzisiaj dziadkami i babciami. Niejeden z nas miał w bliższej lub dalszej rodzinie warszawskiego powstańca. Widziałem obok mnie wielu młodych ludzi, a w ich oczach odbijały się te same uczucia, które i ja w sobie nosiłem". Z posłowia "Przeważał podziw" - refleksje po zwiedzeniu Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego.

Dwie osobne wersje językowe: angielska, niemiecka.

Album powstał przy współpracy z Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego.

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 8

Photographs 20

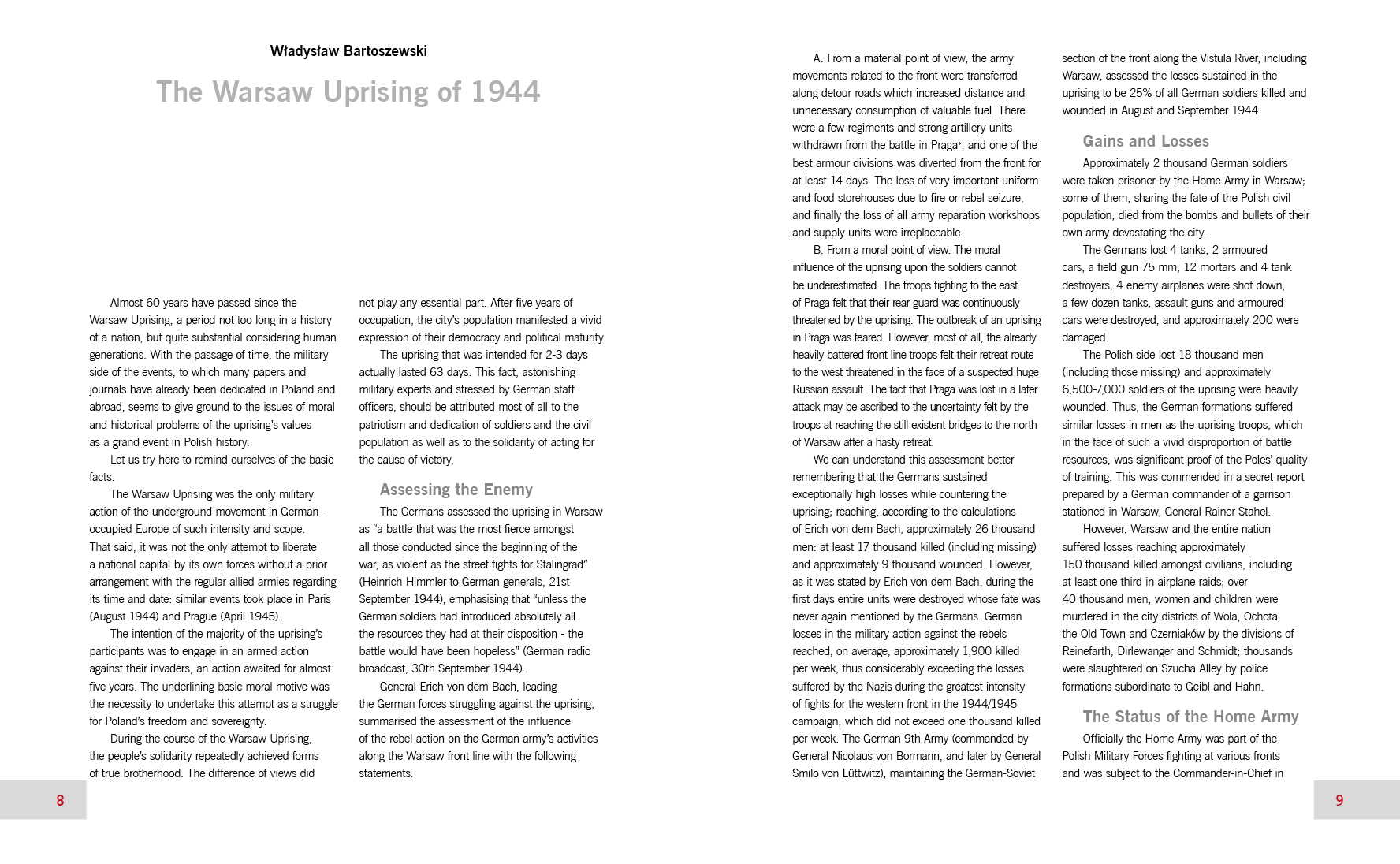

Almost 60 years have passed since the Warsaw Uprising, a period not too long in a history of a nation, but quite substantial considering human generations. With the passage of time, the military side of the events, to which many papers and journals have already been dedicated in Poland and abroad, seems to give ground to the issues of moral and historical problems of the uprising’s values as a grand event in Polish history.

Let us try here to remind ourselves of the basic facts.

The Warsaw Uprising was the only military action of the underground movement in German-occupied Europe of such intensity and scope. That said, it was not the only attempt to liberate a national capital by its own forces without a prior arrangement with the regular allied armies regarding its time and date: similar events took place in Paris (August 1944) and Prague (April 1945).

The intention of the majority of the uprising’s participants was to engage in an armed action against their invaders, an action awaited for almost five years. The underlining basic moral motive was the necessity to undertake this attempt as a struggle for Poland’s freedom and sovereignty.

During the course of the Warsaw Uprising, the people’s solidarity repeatedly achieved forms of true brotherhood. The difference of views did not play any essential part. After five years of occupation, the city’s population manifested a vivid expression of their democracy and political maturity.

The uprising that was intended for 2-3 days actually lasted 63 days. This fact, astonishing military experts and stressed by German staff officers, should be attributed most of all to the patriotism and dedication of soldiers and the civil population as well as to the solidarity of acting for the cause of victory.

Assessing the Enemy

The Germans assessed the uprising in Warsaw as “a battle that was the most fierce amongst all those conducted since the beginning of the war, as violent as the street fights for Stalingrad” (Heinrich Himmler to German generals, 21st September 1944), emphasizing that “unless the German soldiers had introduced absolutely all the resources they had at their disposition - the battle would have been hopeless” (German radio broadcast, 30th September 1944).

General Erich von dem Bach, leading the German forces struggling against the uprising, summarized the assessment of the influence of the rebel action on the German army’s activities along the Warsaw front line with the following statements:

A. From a material point of view, the army movements related to the front were transferred along detour roads which increased distance and unnecessary consumption of valuable fuel. There were a few regiments and strong artillery units withdrawn from the battle in Praga∗, and one of the best armour divisions was diverted from the front for at least 14 days. The loss of very important uniform and food storehouses due to fire or rebel seizure, and finally the loss of all army reparation workshops and supply units were irreplaceable.

B. From a moral point of view. The moral influence of the uprising upon the soldiers cannot be underestimated. The troops fighting to the east of Praga felt that their rear guard was continuously threatened by the uprising. The outbreak of an uprising in Praga was feared. However, most of all, the already heavily battered front line troops felt their retreat route to the west threatened in the face of a suspected huge Russian assault. The fact that Praga was lost in a later attack may be ascribed to the uncertainty felt by the troops at reaching the still existent bridges to the north of Warsaw after a hasty retreat.

We can understand this assessment better remembering that the Germans sustained exceptionally high losses while countering the uprising; reaching, according to the calculations of Erich von dem Bach, approximately 26 thousand men: at least 17 thousand killed (including missing) and approximately 9 thousand wounded. However, as it was stated by Erich von dem Bach, during the first days entire units were destroyed whose fate was never again mentioned by the Germans. German losses in the military action against the rebels reached, on average, approximately 1,900 killed per week, thus considerably exceeding the losses suffered by the Nazis during the greatest intensity of fights for the western front in the 1944/1945 campaign, which did not exceed one thousand killed per week. The German 9th Army (commanded by General Nicolaus von Bormann, and later by General Smilo von Lüttwitz), maintaining the German-Soviet section of the front along the Vistula River, including Warsaw, assessed the losses sustained in the uprising to be 25% of all German soldiers killed and wounded in August and September 1944.

Gains and Losses

Approximately 2 thousand German soldiers were taken prisoner by the Home Army in Warsaw; some of them, sharing the fate of the Polish civil population, died from the bombs and bullets of their own army devastating the city.

The Germans lost 4 tanks, 2 armoured cars, a field gun 75 mm, 12 mortars and 4 tank destroyers; 4 enemy airplanes were shot down, a few dozen tanks, assault guns and armoured cars were destroyed, and approximately 200 were damaged.

The Polish side lost 18 thousand men (including those missing) and approximately 6,500-7,000 soldiers of the uprising were heavily wounded. Thus, the German formations suffered similar losses in men as the uprising troops, which in the face of such a vivid disproportion of battle resources, was significant proof of the Poles’ quality of training. This was commended in a secret report prepared by a German commander of a garrison stationed in Warsaw, General Rainer Stahel.

However, Warsaw and the entire nation suffered losses reaching approximately 150 thousand killed amongst civilians, including at least one third in airplane raids; over 40 thousand men, women and children were murdered in the city districts of Wola, Ochota, the Old Town and Czerniaków by the divisions of Reinefarth, Dirlewanger and Schmidt; thousands were slaughtered on Szucha Alley by police formations subordinate to Geibl and Hahn.

The Status of the Home Army

Officially the Home Army was part of the Polish Military Forces fighting at various fronts and was subject to the Commander-in-Chief in London. Nevertheless, not until 29th August 1944, during the fifth week of the uprising, Great Britain and the United States finally recognised it as a combatant army following the insistent endeavours of Poles. This undoubtedly influenced the treatment of prisoners captured by Germans. Although the Nazi side continued to commit numerous crimes against the participants of the uprising, their frequency in September 1944 visibly decreased. In reality, the Germans did not begin to respect the combatant rights of the rebels until the capitulation of Mokotów (27th September), Żoliborz (30th September) and Śródmieście (2nd October).